This is a personal reflection from Paul Miller, the director of the Haiti Justice Alliance.

I remember very well where I was when I learned that President Aristide had left Haiti in the early morning hours of February 29, 2004. It was my “where were you when you heard JFK was shot” moment, although I have that memory, too. It was at Caribou Coffee in Woodbury, Minnesota and my friend, who had traveled with me to Haiti in December of 2003, 3 months earlier, informed me that news reports were saying that Aristide had left Haiti. “Left Haiti? No way,” was my first thought. I didn’t think that Aristide would ever abdicate his presidential term in Haiti by his own choice after the 1991 coup against him and his 1994 return. Stunned and devastated would accurately describe how I received this most depressing news.

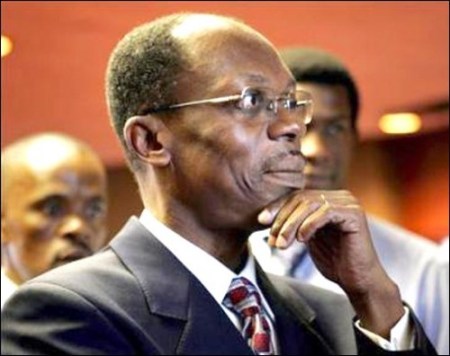

The facts would come to show that my instincts were right. President Aristide had no intention of leaving Haiti on that night or on any night during the remaining time of his presidency. Clearly he did not leave that night of his own volition. You can choose to believe whatever you want to believe about US actions on this or any other given day. However, if you choose to value the truth, then you must accept that the facts show that Jean Bertrand Aristide was removed by US force/s as yet another coup d’état took place in Haiti. The only evidence offered of an alternative scenario are self-serving statements from those at the top of our government, chiefly George W. Bush, Donald Rumsfeld and the sycophantic Colin Powell.

It’s not ancient history, like a lot of our nefarious actions towards Haiti. It was 8 years ago. Monday it was announced that President Aristide is being investigated for drug violations. Our hypocrisy really knows no bounds. What a coincidence that once again we are asked to question Aristide’s integrity and ethics rather than to be reminded that a US-sponsored coup undermined Haiti’s hope for democracy and stability on this day, 8 short years ago.

Posted by Nathan Yaffe

Posted by Nathan Yaffe